Topics

Guests

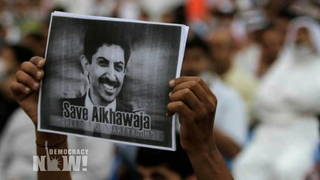

- Maryam Alkhawajaacting president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights and co-director of the Gulf Center for Human Rights.

Bahraini security forces shot dead a teenager earlier today as pro-democracy activists marked the second anniversary of what has been described as the longest-running uprising of the Arab Spring. Since February 2011, at least 87 people have died at the hands of U.S.-backed security forces. We speak to Maryam Alkhawaja, daughter of imprisoned Bahraini human rights activist Abdulhadi Alkhawaja. Maryam has served as the acting president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights ever since the group’s head, Nabeel Rajab, was arrested and jailed. The group has just published a new report titled “Two Years of Deaths and Detentions.” Maryam also serves as the co-director of the Gulf Center for Human Rights. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: We turn now to Bahrain, where security forces shot dead a teenager earlier today as pro-democracy protesters marked the second anniversary of their uprising against Bahrain’s king. Protests are taking place in numerous cities across the country to mark what has been described as the longest-running uprising of the Arab Spring. Daily demonstrations for the past two weeks have called on the U.S.-backed monarchy to address widespread human rights abuses. At least 87 people have died at the hands of security forces since 2011, and thousands more have been injured.

Meanwhile, pressure is growing for the Obama administration to consider relocating the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet from Bahrain in order to push for more accountability on promised reforms. This week, the government held reconciliation talks with opposition parties for the first time in more than a year.

AMY GOODMAN: For more, we’re joined by Bahraini activist Maryam Alkhawaja, who’s currently in Washington, D.C. Her father, Abdulhadi Alkhawaja, the—Bahrain’s best-known human rights activist, has been jailed since the government’s crackdown. Maryam served as the acting president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights ever since the group’s head, Nabeel Rajab, was arrested and jailed. The group has just published a new report titled “Two Years of Deaths and Detentions.” Maryam also serves as the co-director of the Gulf Center for Human Rights, and her sister has been imprisoned, as well.

Maryam, talk about this day, this second anniversary, with yet another killing of a protester, this a teenager.

MARYAM ALKHAWAJA: The repetition of the willingness of the Bahrain regime to use excessive use force against people who are coming out to protest. You know, we were hoping, as human rights defenders, because of the call for a dialogue, that the government would take this as an opportunity to allow people to take to the streets to express their opinions. They knew that people were preparing for going out to protest because it’s the second anniversary of the uprising. But instead, of course, they did what they always do, which is use excessive force against protesters who are taking to the street.

Now, since very, very early morning, protesters have been coming out. It started with people walking to the mosque for morning prayers and were shot at and chased by riot police. And then, since then, we’ve been seeing protests all around Bahrain, almost in every single village. There’s been protests in the capital, as well. And a young boy, Hussain al-Jaziri—he’s only 16 years old—was shot at, you know, very close range with a pellet shotgun, which is usually used for hunting birds, in the stomach. And he died before they could even get him to the hospital.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Now, Maryam, you recently returned to Bahrain after a long period of self-imposed exile. You were able to visit your father and your uncle in jail. Could you talk about how conditions have changed since the beginning of the uprising to currently?

MARYAM ALKHAWAJA: Yeah, of course. I mean, when I left Bahrain, people were still gathered at what was known as the Pearl Square. So it was a completely different scenario that I returned to. You know, I left the country that was full of people that were ecstatic with this demand for freedom and dignity and rights, and you had tens and hundreds of thousands of people on the streets. And I came back to a country where people, even in numbers of 15 to 20 people, could not come out of their houses in a small protest without being attacked by riot police within five minutes. And I saw this with my own eyes.

Bahrain really looked like it had completely turned into a police state. Everywhere you go, there are armored vehicles, there are riot police. You know, you’re at risk of being stopped at a checkpoint at any time. And if you’re from certain groups, from a certain background, you could get completely humiliated, you know, verbally abused during these checkpoints. And also you’re at risk of getting arrested. So, the entire situation, even the feeling of being in the country, has completely changed. There’s this, you know, vast feeling of insecurity and being unsafe.

But then, when you go into the different villages and you meet with the actual people, you see that the spirit has not changed. People still have this belief that no government can outlast its people and that if they decide to continue going, that they want to continue protesting, that it’s only a matter of time before change comes.

AMY GOODMAN: Maryam, can you talk about your sister Zainab, who was arrested as she protested not only your father’s imprisonment but also other relatives and other Bahrainis?

MARYAM ALKHAWAJA: Yes, of course. My sister Zainab, fortunately, was not in prison when I was in Bahrain. She has several cases against her. But, you know, I think Zainab is one of the examples of what the government—when the government doesn’t know how to deal with people. Zainab is one of the people who, you know, very strongly supports the use of nonviolence, you know, using peaceful methods to defy the status quo. And a lot of people have been doing—trying to do the same thing that she does on the streets. The thing is, like, one of the things that I noticed when I was in Bahrain is that you’re—if you have international attention, you’re protected, which is not the case for a lot of people. And I think, you know, to some degree, what Zainab is able to do on the streets, many other people can’t do, even if they wanted, because whereas Zainab might be—you know, they might scream at her, she has been abused before, she’s been arrested, but what would happen to other people who would take the same stand as her would be far worse.

And I remember, you know, I was talking to a former member of torture, who had been summoned and threatened with torture again, without the presence of a lawyer at the interrogation. And when I asked him, “Well, why would you answer any question at an interrogation session without demanding that your lawyer be there?” another victim of torture who was sitting with us started laughing, and he said, “Do you think everyone is Zainab Alkhawaja or Nabeel Rajab? For us, if we demand to see a lawyer, the interrogator says, 'Lock the door. I know how to make you answer my questions.'”

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the U.S. role in all of this, with the Fifth Fleet there? And then talk about Saudi Arabia, as well.

MARYAM ALKHAWAJA: I think, you know, one of the main issues with Bahrain of why the human rights situation keeps deteriorating is because of the lack of accountability. It’s both on a local level and on an international level. When we’re talking on a local level, when we see people, ministers, people in positions like the head of the national security apparatus, who are responsible, even according to the government’s own report, the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry—that they’re responsible for many of the violations that took place in Bahrain, getting—staying in their same positions, or at times even getting promoted, at a time when the government had promised that they will be making reforms and holding people accountable, this is part of the culture of impunity that allows violations to continue happening in Bahrain, just like what we saw today. You know, Hussain al-Jaziri, the way he was killed today in Al Daih is the same way that the first person was killed on the 14th of February, 2011, in the same area, as well, with the use of pellets, Ali Mushaima. So this is the culture of impunity that allows these violations to take place.

And then we see the same thing internationally. The Bahraini regime today believes that they have international immunity. They believe that no matter what kind of human rights violations they commit and they have been committing for the past two years, that they will not be held accountable internationally. And this is because of their relations with certain countries, like the United States, like the United Kingdom. And so, even the most basic steps that were taken against other governments during, you know, these mass uprisings that the Middle East and North Africa region has witnessed, we haven’t seen those steps taken towards Bahrain. If anything, the opposite sometimes happened. Sometimes, you know—we’ve been seeing the selling of arms to Bahrain by the United States and the United Kingdom and others, the ongoing business as usual when it comes to economic deals and so on, and all in the name of security and, you know, the situation in the region. They’re willing to turn a blind eye to the violations of their ally, because, they say, for security reasons. And unfortunately, that’s the same line and the same excuse that Russia uses to continue supporting Syria. Of course, the situations are very different, and the regimes are very different, but the lines that these governments are using to continue supporting a regime that commits lots of human rights abuses are the same lines. And, you know, I think it’s very unfortunate, because the United States—in the short term, this might seem like it serves their strategic interests, but in the long term, this is not sustainable. And if anything, what they’re doing is raising anti-U.S. sentiment in a very, very fast way and also losing credibility in other countries where they are trying to do something about the human rights situation.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And Maryam, on this security issue that you raise, obviously the Saudi monarchy as well as some conservative politicians in this country are arguing against pressure on the Bahraini government, alleging that much of the popular unrest there is being fueled by Iran seeking to stir up the Shia population of Bahrain. Your response to these allegations of Iranian—of Iran being behind the uprising there?

MARYAM ALKHAWAJA: You know, I think that’s—first of all, it’s not—it’s not very difficult to understand what the situation is about in Bahrain. The government’s own report that was brought about by the king and then accepted fully by the king, the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry found—said that they found absolutely no evidence of Iranian influence on the protests in Bahrain.

But even going, you know, beyond that, the Bahraini civil rights movement started in the 1920s, long before Iran meant anything, you know, in the region towards like the security issues, at a time when the Shah was best friends with the royal family in Bahrain. And these uprisings in Bahrain have been happening almost every 10 years since then. This is not something new to Bahrain, the fact that people are going out.

And, I mean, even if you think about it in a very plain and simple way, right? why would people—why would a government that does not allow freedoms and liberties and rights to their own people tell an entire population of another country to go and take to the streets and protest for rights and a civil government and representation and freedom? You know, even the actual—the very basics of the situation would not make any sense for Iran to be involved.

This is about oppression, the fact that the government of Bahrain has been oppressing the people of Bahrain for such a long time that people said, “Enough is enough.” They were inspired by what happened in Tunisia, they were inspired by what happened in Egypt, and they took to the streets to demand their dignity and human rights—and of course Yemen, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: Maryam, we want to thank you very much for being with us. Maryam Alkhawaja is acting president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights. Her father, Abdulhadi Alkhawaja, who was also head of that organization, has been jailed since the government’s crackdown, and she is replacing Nabeel Rajab, who was also head of that organization, who is also in prison right now. She is in the United States on the second anniversary of the Bahrain uprising, after returning to Bahrain for two weeks for the first time since she left in 2011, living in self-imposed exile for security reasons in Copenhagen.

This is Democracy Now! When we come back, we go to Congo to speak with Eve Ensler, founder of V-Day and One Billion Rising.

Media Options